[Note: This post combines three previous blog posts.]

One thing I have learned during my nine years on the Madison School Board is that white families’ attitudes toward race strongly shape their orientations toward our public schools.

The promise of our public schools has always encompassed an egalitarian ideal that our communities would be strengthened as students from all walks of life learn with and from each other. In 1857, D.Y. Kilgore, the first superintendent of Madison schools, approvingly quoted a Massachusetts educator’s description of public schools as “common in the best sense of the word, common to all classes, nurseries for a truly republican feeling, public sanctuaries where the children of the commonwealth fraternally meet and where the spirit of caste and of party can find no admittance.”

Those words were written about a century before Brown v. Board of Education, at a time when the “public sanctuaries” Kilgore celebrated were not equally accessible to students of color. It has proven a tougher sell to promote and celebrate students of all races coming together for learning, in resistance to the social currents that tend to pull white families into their own enclaves and that have fed a national trend toward more segregated classrooms.

Advocates for public schools in diverse communities like Madison are called upon to make the case that white students benefit from attending school with students of color, just as students of color benefit from sharing classrooms with white students. Fortunately, this turns out to be true.

The point has won recognition at the college and university level, primarily as a result of legal battles over admission policies. Last summer, in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the United States Supreme Court affirmed previous rulings and held that colleges have a compelling interest in promoting the racial diversity of their student bodies. The first part of this post draws from the many briefs submitted in the Fisher case to describe the dividends that students can also derive from attending diverse schools at the K-12 level.

Despite the Supreme Court’s endorsement of diversity in college classrooms, the Court has become hostile to race-conscious strategies to address school segregation at the K-12 level. This turnabout from the Court’s earlier support of desegregation efforts has contributed to the growing homogeneity of classrooms throughout the country, a development explored in the second part of this post.

Our state policymakers are indifferent to benefits of diversity in K-12 schools. What’s worse, the usual tools employed to assess the relative quality of K-12 schools in a predominantly white state like Wisconsin have the perverse effect of penalizing diversity.

This ill-serves our Madison public schools. In typical quality comparisons, our schools suffer in comparison to our Dane County neighbors because our classrooms display a level of racial diversity that pays dividends for our students in critical but less quantifiable skills and aptitudes, but not for our schools in standardized test score averages. The third part of this post examines these issues.

Our evaluations and assessment tools should be better aligned with our national priorities. There is a relatively simple way of measuring the degree of diversity in schools and school districts – a Diversity Index – that I describe and calculate for a number of Wisconsin school districts in the fourth part of this post. The post concludes with the recommendation that this type of measure be incorporated into the state’s school report cards and other assessments of school quality.

I. THE BENEFITS OF DIVERSITY

Madison is the most diverse school district in Dane County and probably in Wisconsin, an assertion I explain in the fourth part of this post. We have always believed that a diverse learning environment provides benefits for our students. I have described our graduates as generally more culturally competent and socially adept, more sophisticated in their understanding of racial dynamics, more open to new experiences, and more capacious in their understandings of controversial issues as a result of Madison’s diverse classrooms and the interactions they engender.

But if someone asked me to prove it, I’d have a hard time. Back in 2009, I put together a survey of recent Madison graduates to ask how they felt about the education they received. Many students highlighted the benefits of their diverse classrooms. This was by no means a scientific survey, but the responses were generally consistent with my impressions. Still, that’s more anecdote than evidence.

Help has come from, of all places, the United States Supreme Court. I recently came across “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students,”a February, 2016 study from the Century Foundation. The study has much of value. Particularly helpful was its insight that a treasure trove of data on the benefits of diversity can be found in the many amicus briefs filed with the Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin.

Abigail Fisher, a white student denied admission to the University of Texas-Austin in 2008, sued the university, claiming that its admission policy had incorporated an unconstitutional preference for students of color. The case eventually made its way up to the Supreme Court. Last summer, the Court upheld the admission policy at issue. It reaffirmed the benefits of diversity that it had identified in earlier cases like Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke and Grutter v. Bollinger.

More than 90 amicus briefs were filed with the Court in Fisher. Most of them supported the university, and many of these described the benefits that all of a schools’ students derive from a diverse student body. The amicus briefs frequently observed that their comments presupposed the presence of a critical mass of students of diverse backgrounds; one or two students of color in a class, or a handful in a school, were not enough to provide the benefits that a truly diverse range of perspectives could offer.

The amicus brief of the National School Boards Association, which, like a few other amici, expanded the discussion of diversity benefits to the K-12 level, included a useful taxonomy: “In sum, . . . the educational benefits of diversity in elementary and secondary schools stretch across many realms of student learning and development, including [1] academic achievement, [2] social and interpersonal skills, [3] workplace preparation, and [4] civic engagement.”

What follows is a summary of the Fisher amicus briefs, arranged in the same four categories, along with some survey responses from our students addressing academic achievement and social and interpersonal skills.

A. Academic Achievement

The ways diversity enhances academic achievement evolve as students move through their K-12 years.

In the early school years, when the focus is on skill development, diverse classrooms primarily but not exclusively benefit students of color. The National Education Association (NEA) amicus brief in Fisher describes how students of color do better in reading and math when they are in diverse classrooms (as opposed to classrooms primarily composed of students of color). White students also benefit from the experience of diverse classrooms, which dispel the “otherness” of racial differences for younger learners. The NEA summarizes:

A robust body of empirical research confirms that racially diverse schools and classrooms produce tangible and lasting improvements in academic achievement for minority students, while also benefitting nonminority students. Classroom contact among students of different races also reduces stereotypes and prejudice, and has been found to be more effective in promoting tolerance and cross-racial understanding than any other pedagogical method.

As students grow older and attention turns more to classroom discussion and interactions, the benefits of diversity emerge more clearly. The amicus brief of the American Psychological Association states: “Research clearly demonstrates that exposure to diversity enhances critical thinking and problem-solving ability.” The amicus brief submitted by Harvard explains why: “Students who learn and actively participate in a diverse community must reevaluate received truths, test their own beliefs and biases, and learn to communicate compellingly across differences.” An amicus brief from Brown and other universities adds that diversity “significantly improves the rigor and quality of students’ educational experiences by leading them to examine and confront themselves and their tenets from many different points of view.”

According to the American Psychological Association: “Comparing homogeneous and heterogeneous discussion groups, one study showed that the presence of minority individuals stimulates an increase in the complexity with which students—especially members of the majority— approach a given issue. Members of homogeneous groups in this study exhibited no such cognitive stimulation.”

The Supreme Court was more succinct in Grutter: “’[C]lassroom discussion is livelier, more spirited, and simply more enlightening and interesting’ when the students have the greatest possible variety of backgrounds.”

Our graduates agree. Their responses to my 2009 survey were not written in the formal language of Supreme Court briefs and some reflect a perspective of unacknowledged privilege. But they made similar points about the benefits of attending diverse schools:

- “I think that West offered much better education both socially and academically than the surrounding private and suburban schools. I met and debated with people whose perspectives I never would have heard at a private school and shaped my own views based on a much broader range of opinions. I had more freedom to explore my own identity in a less homogeneous community.”

- “It gave me an opportunity to participate in activities that I never would have gotten the opportunity to participate in otherwise. It gave me a little bit more perspective on the world, and also made me want to learn about other cultures.”

- “Having interacted with more types of people [at Memorial], it broadened my view and allowed me to not jump to conclusions so quickly about people, and see the world through a more global perspective.”

- “[It was] incredibly beneficial. . . . I am used to not agreeing or hearing opinions and perspectives different than my own. This helped me learn to better articulate my own ideas and views.”

B. Social and Interpersonal Skills

Experience in diverse classrooms helps students develop cross-cultural competence, which the amicus brief of Social and Organizational Psychologists defines as “the ability to quickly understand and effectively navigate a culture different from one’s own.”

As explained in the amicus brief of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and other civil rights organizations:

Several research studies have confirmed that cross-racial interactions can increase an individual’s professional competence through fostering openness to opposing points of view, reducing prejudice, enhancing their social self-confidence, and improving their ability to negotiate controversial issues. As a student’s exposure to cross-racial and cultural exchange increases, the student demonstrates increases in cognitive development, self-confidence, understanding, and tolerance. In a survey of over 6,000 alumni of four major research institutions, researchers discovered that those who reported experiencing “substantial” levels of cross-racial interaction in college demonstrated significantly higher skill development in several areas, including the ability to form creative ideas and solutions compared to those who reported only having “some” or “little” cross-racial interaction.

A study cited in Harvard’s amicus brief found that students who reported exposure to diverse opinions, cultures and values developed skills to “work cooperatively with diverse people, discuss and negotiate controversial issues, and engage in perspective taking.”

The American Psychological Association amicus brief reinforced the point:

A critical mass of diverse student groups promotes “the attitudes, knowledge, and skills that prepare college students for meaningful participation in a pluralistic and diverse democracy.” This stems from the development of a student’s cultural competence and “pluralistic orientation: the ability to see multiple perspectives; the ability to work cooperatively with diverse people; the ability to discuss and negotiate controversial issues; openness to having one’s views challenged; and tolerance of others with different beliefs.”

Again, our graduates responding to my survey agree:

- “West offers an intangible, racial and socioeconomic diversity in the student population, that cannot be overestimated and is not typically present in private or suburban schools. . . . [T]he benefits in terms of student growth and tolerance are critically important and will not occur in a homogeneous student body.”

- “I believe attending a high school as diverse as La Follette was extremely beneficial to me. I was exposed to a number of different cultures, both across economic classes and ethnicities. Particularly learning from the Hmong students about how different their lives were helped me to understand just how different someone’s beliefs can be.”

- “Growing up with friends of all backgrounds has made me far more tolerant of different opinions and beliefs, and much more comfortable in situations with diverse groups of people.”

- “East was a pretty diverse school. . . . I think it helped me prepare for adapting quickly to any situation I would encounter in college, and gave me the social skills to fit in pretty much anywhere.

C. Workplace Preparation

The enhanced understandings and aptitudes that students develop in diverse classrooms equip them with skills that are critical for today’s workplaces. The amicus brief of Social and Organizational Psychologists explains:

As American companies have begun to seek out diversity for productivity and profitability, the ability to work within a diverse environment has become an increasingly important skill. Students who function within a complex diverse educational environment develop a deeper understanding of the social world, and develop the cultural-competence skills now necessary for professional success.

The point was underscored powerfully by the amicus brief submitted by nearly half the Fortune 100 companies. The brief states:

[P]eople who have been educated in a diverse setting make valuable contributions to the workforce in several important ways. Such graduates have an increased ability to facilitate unique and creative approaches to problem-solving by integrating different perspectives and moving beyond linear, conventional thinking; they are better equipped to understand a wider variety of consumer needs, including needs specific to particular groups, and thus to develop products and services that appeal to a variety of consumers and to market those offerings in appealing ways; they are better able to work productively with business partners, employees, and clients in the United States and around the world; and they are likely to generate a more positive work environment by decreasing incidents of discrimination and stereotyping.

Amici’s interest in and need for diversity – and, by extension, the state’s interest in diversity in higher education – has become even more compelling as time has passed. American corporations must address the needs of an increasingly diverse U.S. population and a growing global market, and they need a workforce trained in a diverse environment in order to succeed in these arenas.

In Grutter, employers’ recognition of the benefits of diversity contributed to the Supreme Court’s finding that colleges are justified in taking diversity into account in admissions: “These benefits are not theoretical but real, as major American businesses have made clear that the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints.”

D. Civic Engagement

Our goal in Madison is to prepare our students for community, as well as college and career. Our diverse classrooms also help here. As the Brown amicus brief puts it, “[D]iversity benefits society as well, for it fosters the development of citizens and leaders who are creative, collaborative, and able to navigate deftly in dynamic, diverse environments.”

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights amicus brief cites William Bowen and Derek Bok’s 1998 book The Shape of the River, which reports that on a survey of over 27,000 students, the extent of racial diversity and racial interaction among students turned out to be one of the three most influential factors associated with increased student acceptance of other cultures, participation in community service programs, and growth in other aspects of civic responsibility.

The tangible and significant payoffs for civic engagement that result from diverse classrooms are well summarized in the amicus brief of Social and Organizational Psychologists:

Studies measuring the effects of diversity on democracy outcomes show students in diverse learning environments have greater understanding that differences need not be divisive, are more skilled at perspective-taking, are able to perceive commonalities in values between their own and other groups, and show greater interest in politics, participation in campus politics, and commitment to civic participation after college. Further, these students more readily accept conflict as part of normal life. For example, “students who reported frequent contact with diverse peers displayed greater … self-confidence in cultural awareness, development of a pluralistic orientation, believe that conflict enhances democracy, and tend to vote in federal and state elections.”

* * * *

Finally, the academic, skill-building, workplace preparation and civic engagement benefits that Madison students derive from our diverse classrooms are reflected in the amicus brief submitted by Teach For America, the Calhoun School in New York City and a group of other selective and expensive prep schools. The prep schools recognize that exposing their students to genuinely diverse classrooms expands their understanding and hones their interpersonal skills in ways that make their graduates more attractive when they apply to highly selective colleges:

In their long histories of providing and fostering diverse K-12 learning environments, Teach For America, METCO, the Calhoun School, City and Country School and the individual educator amici have observed the benefits of diversity firsthand. They have watched time and time again how students from different backgrounds enhance each other’s academic, psychological and social development. Amici have sent their graduates off to college with not only competitive academic credentials, but also with valuable perspectives on American society and the barriers of race.

Madison students get the benefits of diverse classrooms free of charge – no need to pay the $48,990 tuition that the Calhoun School charges (for high school!).

The academic credentials of our high school graduates vary. Indeed, we have a very pronounced and very troubling achievement gap that we are working hard to address. But because of the rich diversity of Madison’s public schools — which is quantified in part four of this post — our graduates are collectively better prepared for college, career and community than any others in Dane County and probably in the state in terms of the interpersonal skills and expanded understandings that experiences in diverse classrooms nurture.

II. DRIFTING TOWARD HOMOGENEITY

While the benefits of diversity might encourage families to seek out schools with a broad range of students, that inclination often loses out to forces pushing in the other direction. The U.S. Supreme Court’s about-face on the constitutionality of race-conscious approaches to promoting integration has removed the principal counterweight to the centrifugal forces that push white families toward predominantly white schools. Even as courts, scholars, colleges of all stripes, and Fortune 500 companies have been celebrating the many benefits of diverse classrooms, the trend in K-12 education is clearly towards more segregation.

A. The Flow and Ebb of the Supreme Court’s Concern with Segregated Schools.

In Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court emphasized that “education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments,” as it famously rejected the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson and ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In a follow-up decision, the Court ordered states to desegregate their schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Subsequent desegregation efforts focused more on “deliberate” than “speed.” It was not until the Civil Rights Act in 1964 authorized Department of Justice lawyers to sue segregated school districts that appreciable progress began to be made. The Supreme Court’s high water mark in promoting desegregation came in a 1970 decision, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, where it unanimously upheld busing as a permissible means to promote school integration.

With the election of Richard Nixon in 1968, the pendulum started its rightward swing. By the end of 1971, Nixon had appointed four Supreme Court justices. In 1974, the votes of those justices helped overturn a lower court order mandating a desegregation program encompassing inner city Detroit schools and surrounding predominantly white suburbs. Since then, the Supreme Court has been more of an obstacle than an asset in school desegregation efforts.

The nadir was reached in 2007, when in a pair of cases known as Concerned Citizens the Court struck down the plans of school districts in Seattle and Louisville to use race-conscious strategies to maintain the racial composition of district schools at roughly the same percentages as the districts as a whole. The plans at issue were not imposed by the courts – the local school boards had voluntarily adopted them. But the Supreme Court had now become the principal roadblock to school integration efforts, stripping away the authority of local school boards to employ race-conscious strategies.

The federal retreat from desegregation efforts was also evident in the approach of the No Child Left Behind law. It reflected a fundamentally different approach to improving the education of students of color, akin to the “separate but equal” doctrine that the Brown court rejected. The goal of NCLB was to test students to measure their learning, wherever they went to school. The focus shifted from the racial composition percentages of schools to the proficiency percentages of students on standardized tests.

B. The Trend Toward Racially Homogeneous Schools.

The consequences of the federal government’s retreat from the promise of Brown v. Board of Education have been predictable. Without the prod of deliberate desegregation efforts, the racial make-up of public schools has drifted toward homogeneity.

The dissent in Concerned Citizens describes how the rising tide of school integration sparked by Brown v. Board of Education has since receded:

Between 1968 and 1980, the number of black children attending a school where minority children constituted more than half of the school fell from 77% to 63% in the Nation (from 81% to 57% in the South) but then reversed direction by the year 2000, rising from 63% to 72% in the Nation (from 57% to 69% in the South). Similarly, between 1968 and 1980, the number of black children attending schools that were more than 90% minority fell from 64% to 33% in the Nation (from 78% to 23% in the South), but that too reversed direction, rising by the year 2000 from 33% to 37% in the Nation (from 23% to 31% in the South). As of 2002, almost 2.4 million students, or over 5% of all public school enrollment, attended schools with a white population of less than 1%. Of these, 2.3 million were black and Latino students, and only 72,000 were white. Today, more than one in six black children attend a school that is 99–100% minority.

The Fisher amicus brief submitted by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights brings the figures evidencing the growing school segregation trend up to date:

Nationally, the average white student attends a school that is almost 72.5% white, 11.8% Latino, 8.3% black, 3.9% Asian, and 3.5% Native American or multiracial. . . The average black student attends a school that is 48.8% black, 27.6% white, 3.6% Asian, 17.1% Latino, and 2.9% Native American or multiracial. . . Latino students often attend schools that are 56.8% Latino, 25.1% white, 10.9% black, 4.7% Asian, and 2.5% Native American or multiracial. . . The average Asian student attends a school that is 38.9% white, 24.5% Asian, 22.1% Latino, 10.7% black, and 3.8% Native American or multiracial.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, today’s preeminent chronicler of our segregated schools, sums it up:

Legally and culturally, we’ve come to accept segregation once again. Today, across the country, black children are more segregated than they have been at any point in nearly half a century. Except for a few remaining court-ordered desegregation programs, intentional integration almost never occurs unless it’s in the interests of white students.

C. Closer to Home.

In light of the Race to Equity Report, it comes as no surprise that the Madison area does not provide an exception to the national trend. Because Dane County is predominantly white, there is little chance of any of our schools being dominated by students of any other race. Only white families have the privilege of choosing to enroll their children either in schools with an overwhelming percentage of students of their own race, or in more diverse schools.

Any family’s selection of a school can take into account a host of factors. Nevertheless, it is certainly true that not all white parents in Dane County choose to maximize their children’s experience with diverse classrooms. The percentage of white students in Madison’s schools has slowly but steadily been decreasing over the years. White families are substantially overrepresented among those who choose to open enroll their children out of their home Madison schools and into the schools of neighboring school districts. Local realtors tend not to highlight the benefits of increased diversity to white families looking to relocate to the area.

D. White Parents Want to Set Up Their Kids for Success, Most Often with Lots of Other White Kids.

What accounts for the trend toward racially homogeneous schools? Factors are at work that are more nuanced than explicit racism, or, as Slate put it “many white parents, long accustomed to various forms of privilege and preference, fear[ing] their children being in the minority.”

According to an article in the Atlantic:

Some of the most striking studies done on present-day segregation have to do with how it’s connected to the ways families share money and other resources among themselves. The sociologist Thomas Shapiro, for instance, argues that the greater wealth that white parents are likely to have allows them to help out their children with down payments, college tuition, and other significant expenses that would otherwise create debt. As a result, white families often use these “transformative assets” to purchase homes in predominantly white neighborhoods, based on the belief that sending their children to mostly white schools in these areas will offer them a competitive advantage. (These schools are usually evaluated in racial and economic terms, not by class size, teacher quality, or other measures shown to have an impact on student success.) Shapiro’s research shows that while whites no longer explicitly say that they will not live around blacks, existing wealth disparities enable them to make well-meaning decisions that, unfortunately, still serve to reproduce racial segregation in residential and educational settings.

Additionally, white parents in Dane County, like all parents regardless of ideological leaning, want their children to attend schools that will prepare them to be successful. Parents look for highly-rated schools for their kids, particularly when they are moving to a new area and have a choice of where to live. Unfortunately, the scores of the best-known rating organization are unreliable as signifiers of school quality.

III. THE PROBLEM WITH SCHOOL RATINGS

The ways we typically rate schools undervalue the benefits of diversity and overrate schools with a high percentage of white students.

There are a couple of key reasons for this. First, it is not easy to measure and quantify the understandings and skills that immersion in diverse schools engenders in our students. We can say diversity provides benefits all we want, but – short of citing Fisher amicus briefs – we haven’t had much that’s concrete to back up our claim. This makes it a challenge to persuade those in Dane County who are not already convinced that diversity in our classrooms is a good thing for all students.

Second, quantification and measurement is exactly what standardized tests do. On an aggregate basis, students of color score lower than white students on standardized tests. An exploration of the reasons for this – and there are many – is well beyond the scope of this post. But when schools are ranked strictly on the basis of standardized test results – as they often are – diversity flips from an asset to a burden.

Here is an example based on data from the 2014-15 school year. Suppose you wanted to compare the academic performance of the students at two of the top-notch high schools in the area, Madison West and Middleton, for that year. The information to do so is available on the DPI website. You can learn how the students at each school did by looking at the ACT Statewide data. You would see that the average ACT score for Madison West students was 23.2, compared to 23.6 for Middleton students. So Middleton students did better, right?

Well, not so fast. Let’s dig a little deeper. Let’s look at 2014-15 average ACT scores by racial/ethnic group, also as reported by DPI:

Madison West students did better in every category where there is a basis for comparison. (The number of Madison West students of two or more races who took the test was below the threshold for DPI to calculate an average score.) So why does Middleton have the higher overall average? This outcome is completely determined by the demographics of the schools. There are more West students than Middleton students in the lower-scoring categories, and this effect overwhelmed West’s clear superiority in the category-by-category comparisons.

There is more evidence of diversity’s negative impact on school comparisons all around us. For example, Google “best schools in Dane County.” You’ll get greatschools.org, or perhaps Zillow, which incorporates GreatSchools ratings. GreatSchools assigns a rating on a 1-to-10 scale to every school around. From all that appears, the GreatSchools ratings are the most commonly referred to sources of information about the relative quality of schools available to newcomers to our area or those contemplating relocation.

The GreatSchools rankings of Dane County schools appear to be entirely based on the results of standardized tests, undifferentiated by school demographics, income levels, or anything else. Not surprisingly, there is a substantial diversity deduction in these rankings. To understand why, we need to focus on how the ratings reflect the achievement levels and preponderance of white students at our schools.

Looking at the standardized test scores of white students provides an evenhanded if partial basis for comparison, unaffected by the schools’ differing demographics. In addition, it is the white families in the Madison area who are in the best position to affect the level of diversity in our schools, primarily through their choices of whether to enroll their students in Madison public schools or suburban or private alternatives. In light of this, it makes sense to tailor the analysis to the considerations that would be most relevant for them, in part so that we can have some basis to assess the validity of a “school quality” explanation for choosing a non-MMSD school.

The following tables shows three data points for the high schools in the Madison area: 2015-16 average composite scores for white students taking the ACT Statewide exam administered to all students in grade 11; percentage of the student body comprised of white students; and GreatSchools ranking on its 1-to-10 scale.

| High School |

Average ACT Score for White Students |

Student Body % White |

GreatSchools Rating |

| DeForest |

21.1 |

84.1 | 9 |

| East |

23.8 |

38.5 |

3 |

| LaFollette |

21.5 |

40.6 | 2 |

|

McFarland |

23.4 | 84.9 |

10 |

| Memorial |

24.6 |

51.1 | 6 |

| Middleton |

24.4 |

77.9 |

7 |

| Monona Grove |

23.0 |

85.1 |

8 |

| Mt. Horeb |

22.3 |

91.5 |

9 |

|

Oregon |

22.5 | 89.1 |

7 |

| Stoughton |

21.5 |

88.2 |

9 |

| Sun Prairie |

22.6 |

69.0 |

9 |

| Verona |

23.1 |

67.7 |

8 |

| Waunakee |

23.3 |

91.9 |

9 |

| West | 25.4 | 53.3 |

7 |

It turns out that the GreatSchools ratings bear no relationship at all to the average composite ACT scores earned by white students at the different high schools, which presumably would be data of interest to white families seeking to relocate to Madison.

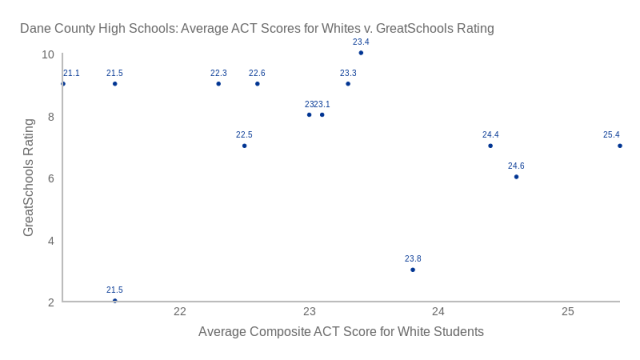

Here is a table that plots average composite ACT scores for white students on the X axis and GreatSchools rating on the Y axis for each of the high schools:

There is a very weak correlation of -0.1208, which is far from statistically significant. Inconveniently for GreatSchools, the correlation, such as it is, is negative – the higher the average ACT score, the lower the GreatSchools rating. This upside-down result is driven by the low ratings assigned to Madison’s four high schools (no non-MMSD high school is rated lower than any MMSD high school). This despite the fact that three of the four schools with the top ACT scores are West, Memorial and East. East, the most diverse high school in the area, is a particular outlier on this table.

It is certainly instructive that we obtain a far more robust correlation when we plot the percentage of the high school’s student body comprised of white students against the GreatSchools rating:

Here we get a statistically-significant positive correlation of 0.8356 – which means that high GreatSchools ratings are strongly correlated with high percentages of the student body comprised of white students.

In other words, in doling out its top ratings, GreatSchools doesn’t particularly care how well white students perform, as long as there are lots of them at the school.

This is not a statistical aberration confined to high schools. For elementary schools in the Madison school district, there is also a strong positive correlation of 0.7559 between the GreatSchools ratings and the percentage of the school’s student body that is white.

So, in the most widely available rating system for schools, Madison’s public schools are effectively penalized for their diversity. This doesn’t make sense, it certainly undermines whatever confidence one might have in the GreatSchools ratings, and it hurts our schools.

It is the same with the state’s school report cards. Pursuant to a legislative mandate, DPI prepares report cards for each Wisconsin school and school district that include an overall score on a 0 to 100 scale. As I have written, while the report card methodology includes measures that attempt to take student demographics into account, overall student performance on standardized tests remains the driving force behind the scores for each school and school district.

The DPI report cards do better dealing with diversity than the GreatSchools ratings, but the methodology still falls short. There is a moderate (0.622) but statistically-significant correlation between DPI report card scores for school districts in Dane County and the percentage of white students in those districts.

IV. IF WE VALUE DIVERSITY IN OUR SCHOOLS, LET’S KEEP SCORE.

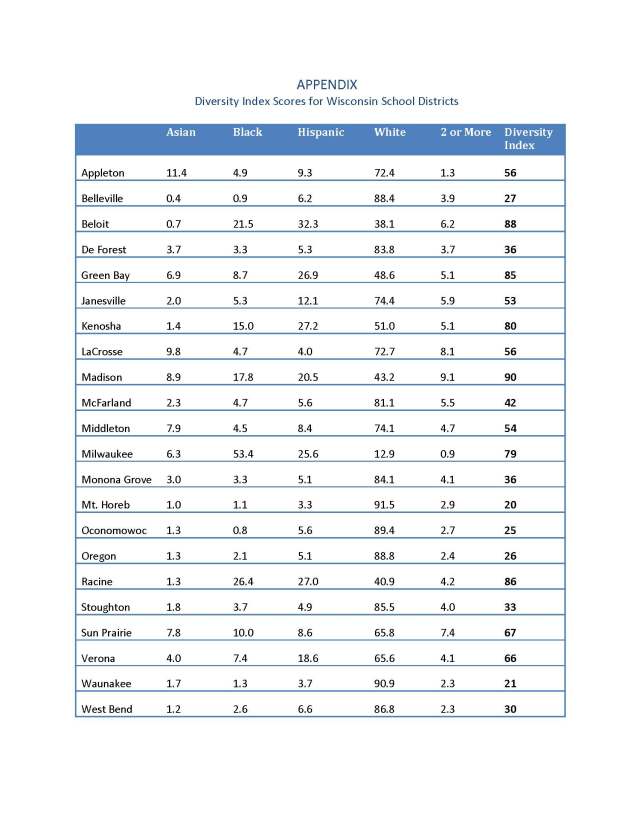

I propose a modest corrective to the tendency to undervalue diversity in school ratings. Along with its 100-point-scale “Report Card” score for Wisconsin school districts that it prepares each year, the Department of Public Instruction should also prepare a Diversity Index calculated on a similar 100-point scale.

Before delving into the Diversity Index, several points are worth noting. First, the negative diversity effect on school comparisons discussed in the third part of this post derives less from racism than from the unavoidable tendency to base comparisons on whatever it is that can be measured and quantified. Standardized test results provide the handiest and easiest basis for school comparisons and so it is inevitable that they will be used that way.

Second, standardized tests are not inherently bad. The basic skills they measure are critically important to school success. Year-to-year comparisons of test results can provide valuable insights for teachers and schools. So can school-to-school comparisons, so long as the schools are otherwise comparable.

Third, as noted in the third part of this post, on an aggregate basis, students of color tend to score lower than white students on standardized tests. This aggregate effect says next to nothing about the skills and potential of individual students, but its impact must be acknowledged in order to unpack the misleading tendencies of school rating systems that are primarily based on an undifferentiated analysis of standardized test scores.

Fourth, the impressive data marshaled in the many Fisher amicus briefs leave no doubt about the non-quantifiable benefits of diverse classrooms. More encompassing and accurate methods of school evaluation and comparison should take diversity data into account. The goal should be to make smart use of that information to supplement quantitative methods of comparing schools in order to provide a more comprehensive assessment of school quality.

Fifth, we do not have ready means to measure the growth in interpersonal skills, workplace preparation and civic engagement that we know exposure to more diverse learning environments provides to students. In recognition of this gap, it makes sense to rely on diversity data itself as a proxy for the beneficial outcomes that diverse classrooms engender.

Finally – and here comes the partial remedy – it is not hard to develop a metric that represents the level of diversity in schools and school districts.

In antitrust law, the relative concentration of any particular market for products or services is measured by what’s called the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI. The index is calculated by determining the market percentage shares of the participants in the market, squaring those percentages, and adding up the total. So, for example, if a market is entirely monopolized by one firm, its HHI would be 10,000. If the market features two firms, each with a 50% share, the HHI would be 5000. If there are six market participants with shares of 40, 20, 15, 10, 10 and 5, the HHI for the market is 2450.

A similar calculation can be applied to measure the diversity of any school district or school. DPI measures race or ethnicity in five principal categories: Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and Two or More Races. An HHI figure can be calculated by adding up the squares of the percentages of a school districts’ students that fall into each category. (DPI also includes American Indian and Pacific Isle in its race/ethnicity categories, but the percentages are so small that they can be disregarded for these purposes.) The lower the HHI, the greater the school’s diversity.

In the interest of consistency, it makes sense to convert HHI figures for school or school district diversity to the same kind of 0 to 100 score that is used in DPI’s school report cards. We can call it a Diversity Index. A Diversity Index can be calculated, first, by subtracting a school diversity HHI from 10,000 and, second, dividing the result by 100. The highest possible score under this formula is 80, since the lowest possible school diversity HHI is 2000 (the result when exactly 20% of a school’s students fall into each of the five primary DPI racial/ethnic categories). The results can be grossed up to the traditional 0-to-100 scale by multiplying by 1.25 the figure derived by subtracting the HHI number from 10,000 before dividing by 100.

Here are Diversity Index scores for large urban school districts in Wisconsin. The underlying data can be found in the Appendix, but the scores are based on DPI data for the 2015-16 school year, calculated as described above, and arranged from highest to lowest:

Here are Diversity Index scores for the principal school districts in Dane County, again from highest to lowest.

I have not calculated the Diversity Index for each school district in Wisconsin, so I cannot say for sure that Madison is the most diverse school district in the state. But it does seem likely.

SUMMING UP

Truly diverse classrooms provide substantial but non-quantifiable benefits for all students. Recognizing the benefits, colleges and universities seek out and celebrate diverse student bodies.

But we have essentially given up on promoting diversity and integration as deliberate educational policies at the K-12 level. Instead, we defer to individual parent choice as matter of policy, which for these purposes means the choices of white parents.

While in the words of Nikole Hannah-Jones, diversity finds support as “a boutique offering for the children of the privileged,” most white parents implicitly or explicitly view a predominantly white student body as a key component of school quality.

This understanding is misleadingly reinforced by school rating systems that systematically undervalue the benefits students derive from diverse classrooms and systematically inflate the ratings of schools that are already dominated by white students.

By implicitly acknowledging diversity as an asset and providing clear, meaningful and helpful information about the degree of diversity in Wisconsin’s school districts, the Diversity Index can serve as a modest counterweight to these skewed rating systems. DPI should include Diversity Index scores with its school and school district report cards.

Inclusion of the Index in the report cards will not remedy the report cards’ shortcomings. But it will help to put them in context in a way that will make the report cards more informative for those interested in accurate and comprehensive comparisons of school quality.

Issuing Diversity Index scores for Wisconsin school districts will also send the message that genuine classroom diversity is beneficial and undervalued, indicate that the relative degree of diversity in our schools is important enough to measure, and a represent a step toward honoring the broader public purpose of our public schools.

Have you thought of submitting this for publication in an academic journal?

Thanks, Leonard. I’m afraid this isn’t academic enough for an acedemic journal and much too long for just about anything else. If I were promoting voucher schools or some conservative cause, there would be a lot of potential outlets for something like this. Unfortunately, there ‘s a lot less for pieces that argue the other side.

Damn you’re good.

Thanks, Brian!

Paul Fanlund’s article lead me to this superb piece Ed. Thank you so much. I think it’s brilliant, and rightly points to the positive value of diversity. Unfortunately, as you point out, overall test scores penalize diversity, to the extent that they reflect larger proportions of students of color that generally score lower. Ironically, this phenomenon plays out when examining NAEP scores (the primary test that allows comparisons across states). Wisconsin does deceptively well relative to the US, thanks partly to it’s lack of diversity. Just as you found with West vs Middleton High, for example, a comparison of 8th grade math scores finds Texas scoring higher than Wisconsin in every race, yet falling below Wisconsin overall because of the racial distribution.

I really liked your Diversity Index, and the adjustments you make to the “HHI”. I ran the numbers Ed, and you’re right, Madison is the highest scoring district in the state. Beloit comes in 2nd, Racine 3rd, & Brown Deer 4th (not sure how to attach file; my numbers slightly differed from yours, but I don’t believe your race distribution totals equal exactly 100). Interestingly, Madison’s index is very close to that of the nation: the US index, looking at 4th grade & 8th grade NAEP takers, is around 81; the Wisconsin state total is 57.

Really nice work here. Glad I followed the paper link to this blog. I have been thinking of this issue for nearly a decade now. I have a few thoughts to add.

I can’t fully jump into what this blog is suggesting. Even though I agree with much of it and started my interest in this back during the ACT 10 ordeal and looking at the comparisons between Texas and Wisconsin standardized test scores. In that case Texas (non union teachers) had better comparisons across their racial groups than Wisconsin did. In effect Texas was the MMSD and Wisconsin was the Dane County suburban schools.

Thoughts and questions.

1) What is diversity? Based on what I am reading here it is simply skin color. Period. I think those boxes that we are placed into based on simply skin color are way too limiting. Wayyyyy too limiting.

This buzz word has become a self righteous band aid to many people it seems. Diversity in and of itself does not make a place great. Exceptionalism makes a place great. I do appreciate the studies that were in the blog and I do agree that this information is hard to quantify. I have too many questions yet to consider on this.

2) Safety and culture. Honestly if you could show that the culture at minority heavy schools is appropriate and as safe as the white heavy ones, that would go a long way. I just see a lot of nonsense behavior going on in many schools and it seems to be worse in the minority heavy schools. Not all cultures are equal in every way and not all deserve celebration or exposure to our kids. Sure, exposure to different cultures may help a student relate to different people in the future, but parents will also wonder if bad elements of different cultures will rub off on their kids. I believe the vast majority of parents would send their kids to an affluent high diversity of skin color school, vs a very poor homogeneous school, regardless of races involved. Culture and safety trump skin color I believe. Now the numbers may prove that wrong, and I would be interested in digging further into it.

3) This blog continually words the common standardized testing rankings as “penalizing diversity.”

I am not attacking the author here because I truly find the material compelling and am interested in a discussion of greater depth……but….isn’t that phrase a bit…misleading? Doesn’t that imply that all whites perform at a certain level and all hispanics, etc? These rankings penalize performance, period, and do not care what the skin diversity is. Are skin diversity ratios the main factor here in the rankings or do economic conditions play a greater role?

4) By the numbers that are presented here a white family should send their kids to MMSD schools because 3 of the top 4 test score schools at the high school level are from MMSD if you just look at the white kids scores. I would guess that most parents in Dane County would be shocked to see these numbers, especially Madison East! (kudos to them btw) What are the other population’s numbers compared across the schools besides West vs Middleton? Again, if #2 above could be looked at closer and parents more reassured about their little darlings, then the flight may diminish.

5) Madison schools are physically not in as good of shape as their suburban counterparts. It is night and day. Those kind of impressions matter greatly (right or wrong) to many families. This contributes in some way to the flight, especially for families new to the area. People want the impression that their kids goes to a nice looking, modern, great school. Madison may allocate more of its resources to support staff than into facility updates- but that has consequences in multiple ways.

I am rambling. But thanks for the blog. Great stuff!